The impact of William Laud and the positioning of the Altar

Watch a short video of Dr Stewart Mottram discussing the positioning of the Altars at All Saints’, and scroll down to read more.

In the 1620s and 1630s, Charles I’s Protestant religious advisor, William Laud (Archbishop of Canterbury from 1633) had a great impact on the Church of England and the appearance of All Saints’. Rector Henry Wickham’s role as Archdeacon of York involved imposing Laud’s concept of the “beauty of holiness” on parishes. This included church improvements, enforcing use of the Book of Common Prayer (to reduce preaching), and showing greater respect for the sacraments. This was especially challenging in the mainly Puritan city of York where Archbishop of York (1632-40) Richard Neile was equally associated with so-called ‘Laudian’ reforms. Neale effectively worked in tandem with Laud, introducing and enforcing ‘Laudian’ innovations across York archdiocese. For example, he was the first bishop to order that communion tables be railed in, and it is written that ‘Over three-quarters of the churches and chapels in the northern province are known to have been repaired and ‘beautified’ during the 1630s.’

Laud wanted strict uniformity within the Church and no deviation from what he wanted. The Presbyterians in Scotland were angered by Laud when he ordered that they had to use the English Prayer Book for their services. The Scots made it clear that they were willing to fight to preserve their rights and in 1639 an army crossed the border and attacked north-eastern England. It was a period of great unrest and the association with Roman Catholic mass fuelled anger and was a contributory cause of the First English Civil War (1642-46).

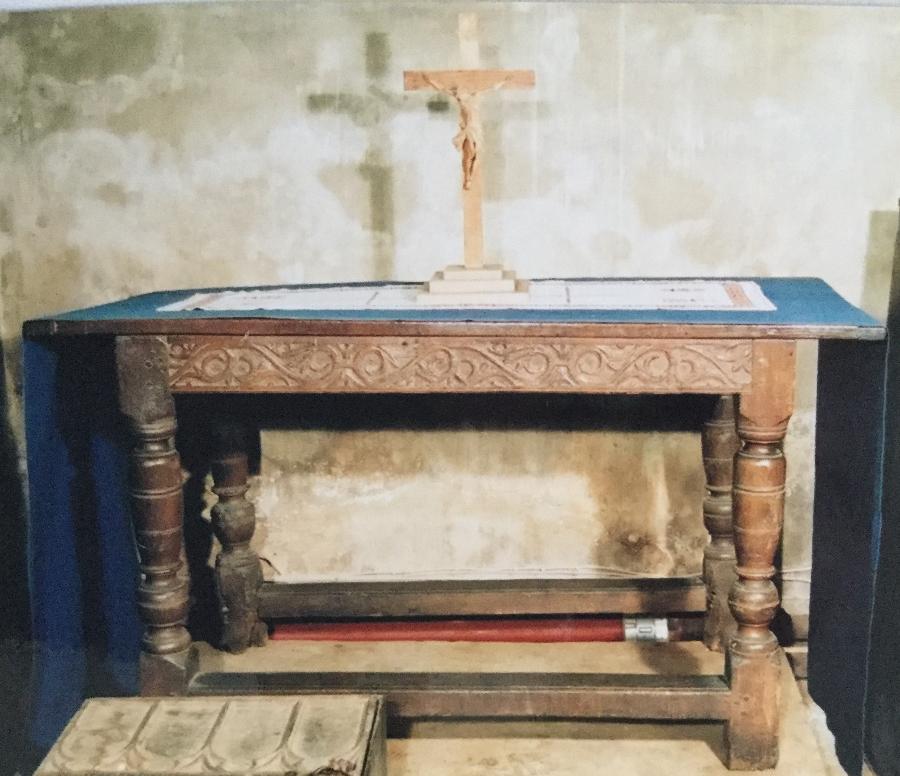

The ornate font cover at All Saints’ reflects Archbishop Laud’s desire to show greater reverence for the sacrament of baptism. The uniform box pews, replaced an earlier haphazard collection. The communion table also reflects Archbishop Laud’s controversial Altar Policy which aimed to show greater respect for Holy Communion. In 1635, parishes in Yorkshire had to move their altars to the east end and rail them, to protect them from the attentions of dogs and children. All Saints’ Bolton Percy also has its original early 17th Century wooden communion table (see photo below), as well as the now more conventional ‘Laudian Altar’ underneath the East Window.

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm can be defined as the intentional desecration or destruction of works of art, especially those containing human figurations, on religious principles or beliefs. More general usage of the term signifies either the rejection, aversion, or regulation of images and imagery, regardless of the rationale or intent.

Considering Parliamentarian soldiers were billeted at All Saints’ during the Civil War, the absence of significant iconoclasm is surprising. Evidence of their stay includes damage to the chancel stalls caused by soldiers sharpening their swords, musket ball marks on the exterior walls and the name of a supposed Parliamentarian soldier, Richard Akroyd, carved into a return stall. This may have been a disrespectful act, or equally that of a soldier uncertain of his fate, marking his existence before being led into battle by Ferdinando Fairfax at Marston Moor.

In August 1643, Parliament ordered that images of Christ, the Virgin Mary and of the saints should be destroyed, however these survive at All Saints’. At that time All Saints’ was a significant church within the York diocese and it is possible that Ferdinando and his son, Thomas Fairfax, protected the stained glass like they had for York Minster.

Here you can watch a short video of Dr Stewart Mottram discussing how Iconoclasm might have affected All Saints’.